It was shortly past noon in the peaceful town of Milbrook when an unexpected knock on the door of Dr. Ethel Glenfield’s office altered the course of what had begun as an ordinary day. The morning had passed in familiar quiet: the gentle clinking of teacups, soft murmurs between Dr. Glenfield and her colleague, Dr. Featherstone, and the routine hum of scholarly work. Both historians had devoted decades to piecing together Milbrook’s past, poring over old letters, manuscripts, and town records. Yet nothing in their experience had prepared them for the brown paper package that had just arrived.

A young messenger, scarcely older than a boy, handed over the parcel with a nonchalant shrug and a mumbled apology for the delay. He offered no explanation. Dr. Glenfield signed for the delivery, curiosity immediately replacing the slight apprehension she had felt moments before. Together with Dr. Featherstone, she gathered around her desk, the air thick with anticipation and unease.

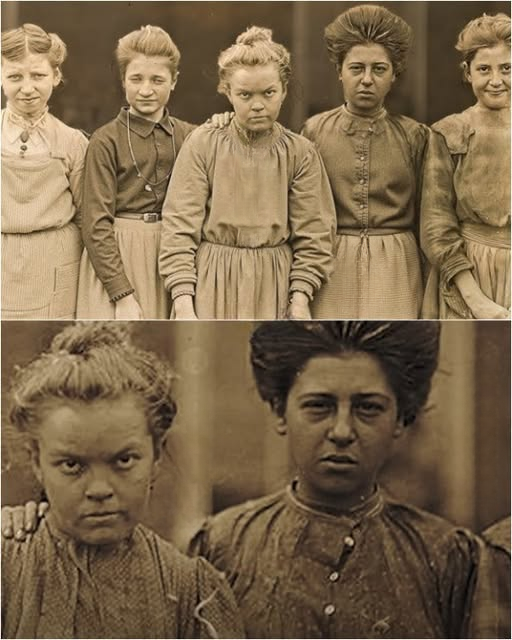

Carefully, Ethel tore back the paper. Inside rested a daguerreotype, the silvered plate glinting faintly in the afternoon light streaming through the office window. The photograph captured five young girls, their faces frozen in time through one of the earliest forms of photography. Daguerreotypes are renowned for preserving not just images, but the very essence of their subjects, and this image was no exception.

Attached to the photograph was a note from the local historical society. Dr. Featherstone read it aloud:

“They’ve requested our expertise… regarding an estate on the outskirts of town.”

Ethel’s hand trembled slightly as she raised the plate to the window, adjusting her wire-rimmed spectacles. Five faces stared back, their expressions serene yet haunting. Something about the girls felt familiar, though Ethel could not immediately place why. Each girl, no older than sixteen, stood in perfect alignment, suggesting careful orchestration by the photographer. The background, blurred in the soft, characteristic tones of early photography, hinted at a quiet, almost pastoral scene.

Reaching for her magnifying glass, Ethel examined each face. The first girl, chestnut-haired with carefully braided plaits, smiled gently. Her simple but neat attire suggested modesty or careful thrift. Beside her stood a girl with similar features, her reserved expression hinting at quiet thoughtfulness. The middle sister, upright and honey-haired, seemed tense, as though bracing against some unseen weight. The fourth, with dark hair and keen eyes, appeared intensely watchful. But it was the fifth girl, positioned at the far right, who drew Ethel’s attention most. Her radiant smile and youthful energy set her apart, her casual bun and glowing features hinting at a unique vitality.

Dr. Featherstone leaned in, noting the precision of the girls’ posture. “It looks like a formal assembly,” he mused. “Could this be more than just a family portrait?”

Ethel’s heartbeat quickened. “There’s something… extraordinary about these faces,” she murmured.

For hours, the historians examined the daguerreotype in painstaking detail. They scrutinized postures, clothing textures, and subtle reflections on the silvered plate. Dr. Featherstone was the first to spot a clue:

“I believe these two are sisters,” he said, pointing to the first and last girls. There was something distinct in the youngest girl’s complexion—a hint of mixed heritage, unusual for the time, suggesting an extraordinary story behind the family.

Ethel’s mind raced. She retrieved a thick genealogical volume, flipping through meticulously transcribed records, birth certificates, and family trees. Slowly, a pattern emerged: the Clifton family. Five daughters, born between 1830 and 1833—Edna, Lucy, Mabel, Kate (twins), and Rose. Rose, the youngest, had been adopted after her mother, a freedwoman, died in childbirth. The Clifton family, devout Quakers and active supporters of the Underground Railroad, had raised her alongside their biological children.

Recognition hit Ethel like a wave. The faces before her were not simply a family record—they were a testament to a family that lived its values, embodying compassion and courage far ahead of their time.

The Tragic Fate of the Cliftons

Further research revealed the tragic end of the Clifton family. In the winter of 1847, a fire claimed the lives of the entire household, including all five daughters. Known for their charity, music performances, and unwavering kindness, the Cliftons were pillars of the community. Their deaths left a void that lingered in local memory, their lives remembered with both admiration and sorrow.

The daguerreotype, therefore, was more than a family portrait—it preserved the legacy of five young women whose lives had been defined by courage, empathy, and devotion to others. Yet the photograph held further secrets. Upon closer inspection, children appeared in the background, slightly blurred but increasingly distinct. Their ages appeared almost identical, suggesting a deliberate documentation of a significant event rather than a casual gathering.

“Featherstone,” Ethel whispered, awe in her voice, “look at the children in the background. They’re nearly the same age.”

Etched faintly in the corner of the plate were numbers: 8:15:1836. August 15th, 1836. Dr. Featherstone read aloud, astonished. “That’s years before the Clifton house fire… why would the girls look… worn?”

A Heroic Rescue

Ethel turned to the local archives and found an account that explained the scene. On that date, the Clifton sisters had rescued fourteen children from a clandestine holding facility, an early form of child trafficking. The sisters had spent three days at the site, providing care, comfort, and sustenance before authorities intervened.

The daguerreotype, then, was a formal record of one of the earliest documented child rescues in American history. The dirt on the girls’ clothing, the mix of exhaustion and resolve, and the precise composition of the image were proof of their bravery and compassion.

Ethel’s phone rang. It was Paloma McKinley from the historical society:

“Dr. Glenfield, have you examined the photograph?”

“Yes,” Ethel replied, her voice heavy with emotion. “It’s remarkable. This isn’t simply a family portrait—it documents extraordinary humanitarian action nearly two centuries ago.”

Paloma whispered, “My God… this predates much of what we thought about integrated family histories in pre-Civil War America.”

Piecing Together History

Ethel and Featherstone spent days cross-referencing genealogical records, newspaper reports, and legal documents. Each detail confirmed the story: the Clifton sisters had risked their lives for vulnerable children, defying societal norms and legal barriers of their era. Their legacy, immortalized on the silvered plate, offered a glimpse into an America often overlooked in mainstream accounts—an America where moral courage, social justice, and humanity flourished despite prejudice.

The daguerreotype had captured more than faces; it preserved an ethos of bravery and service, a family committed to justice, equality, and community welfare. Even after nearly two centuries, the Clifton sisters’ story resonated with clarity and moral force.

The Daguerreotype Today

Today, the photograph holds a place of honor in Dr. Glenfield’s office, not merely as an artifact but as a living testament to the power of human courage and compassion. It serves as a reminder that history is never static; each image, each document, has the power to reshape understanding, challenge assumptions, and inspire future generations.

Sharing their findings with the historical society, Ethel and Featherstone ensured the story of the Clifton sisters reached a wider audience. Scholars, students, and local residents could now witness a family that lived its values with extraordinary integrity, leaving a legacy that transcended tragedy.

The daguerreotype remains a delicate yet enduring record: five sisters, united not just by blood but by compassion, courage, and an unwavering commitment to justice. Their story reminds us that history is made by the choices of ordinary people who dared to act with extraordinary humanity.